As I’ve previously mentioned, I volunteer at the Bisexual Resource Center with their communications and policy & advocacy committees. With March being Bisexual Health Awareness Month, I had the honor of being invited to write a blog about my experience with the healthcare system as a Bi+ person. Below is my article directly on the BRC website!

Category: Writing

International Bisexuality Research Conference

Back in September I presented my master’s thesis research at the International Bisexuality Research Conference. I meant to post about this earlier but the livestream recording wasn’t posted to YouTube until recently.

My talk was entitled “How Do We Know You’re Actually Bisexual?”: The Function of Inclusionist and Exclusionist Ideologies on Tumblr but autocorrect ended up changing “Inclusionist” to “Illusionist” on accident. I summarize my master’s thesis research and answered some questions about researching biphobia online moving forward.

I am very thankful I had the opportunity to present my research at an international conference! It was a great time and all of the other presenters were amazing!

Check out the rest of the presentations here or their website here!

Talking in the Tags: An Exploration

Preface: Much of my research focuses on the social media platform Tumblr and its user base. As a person who has been using Tumblr for around a decade now the intricacies of platform use are always changing. I wrote this piece while thinking about the phenomena of “talking in the tags” especially as it is not something that is seen on other platforms.

I love “talking in the tags” on Tumblr. It blurs the line between public and private while providing the space for me to comment on content without adding on to the post itself. But other platforms do not use tags in the same way they are used on Tumblr. The organization of social media platforms generally relies on a tagging system where a word or a phrase is entered with a “#” in front. Using “a pound sign in front of a word signals to audiences that it was intended to be findable by anyone who searched for it,” which has been incorporated into most social media platforms. (Daer, Hoffman, & Goodman, 2014, 1) When users “perform a “search” for a particular word or phrase… all the posted tweets using that hashtag will appear” and, more recently, any posts that use the words within the hashtag. (Ibid)

Across platforms, tagging has different functions and different meanings. Tagging functions as both an organization system and a way to be known, especially on platforms where one can monetarily profit from being “internet famous.” Tumblr as a platform complicates both tagging and profiting off internet status, changing the context of tagging and its function. Instead of using tags to promote oneself, Tumblr uses the tags as a semi-private space to add commentary without adding to the post itself. “Talking in the tags” changes the context in which we can understand tagging where the usage is less about promotion and categorization and more as a space where one can comment within an area where only one’s followers will see the comments instead of everyone who comes across the post.

Tagging creates a public conversation where the inclusion of a tag in a post also means the inclusion in a larger conversation. (Zappavigna & Martin, 2018, 1) Users create the content and use tags to either organize their posts or promote their content and group it with those who create similar content. Using tags is critical for gaining exposure for “influencers” or people making money from social media because those who follow a tag will be more likely to engage with your work. Tumblr creates an interesting problem when studying social media platforms and their functionality, as there is no way to build a career from Tumblr. One could make money by having a popular Instagram, YouTube, or even Twitter account, but “Tumblr famous” cannot monetize that fame. Where tagging systems can promote one’s work to a wider audience, Tumblr’s tagging and search system barely function, so tagging to advertise is not a common practice. Besides “talking in the tags,” the primary use of tagging is for others to block content they do not want to see. Tags for blocking can either be prefaced with a Content Warning (CW) or Trigger Warning (TW) and can go hand in hand with someone tagging to organize their blog. Combining tagging for organization and blocking purposes is not required by the platform but is proper etiquette. Due to the anonymous messaging system on Tumblr, users can get messages requesting that things be tagged. As a platform, Tumblr takes what people understand as the function of tagging and shifts it from a space strictly for the organization to a semi-private space of commentary.

For my research on inclusionist and exclusionist queer discourse on Tumblr, my primary mode of data collection is to search for tags on Tumblr. As outlined earlier, the problem with tagging on Tumblr is how people do not tag to categorize posts or optimize their searchability but instead to comment/”talk in the tags” or as organization on their blog. Often, searching through tags is more of an exploration of what people tag rather than what is being said. Even in original content where the original poster (OP) has the space to make whatever public declarations they desire, there is still “talking in the tags” where a more private or even controversial idea gets expressed. Non-organizational tagging plays “no role in enhancing the visibility and searchability of a post and would not be considered metadata labels like keyword tags,” which creates privacy. (Bourlai, 2018, 2) But “talking in the tags” does not always stay in the tags as people will copy and paste or ever screenshot tags to add to the original post. “Talking in the tags” exists in this space that is both private and public and does not fit with the ability to search for a tag as they are often too specific, or Tumblr’s search function won’t acknowledge them.

“Talking in the tags” presents both an opportunity to understand the differentiation between posting for a general audience and posting for a specific audience while also complicating the idea that tagging is strictly an organizational system. Approaching the tags on Tumblr as a semi-private space calls into question what parts of one’s online life are meant for the consumption of others. Tumblr adds a different context to what tagging means, especially as people accustomed to tagging systems outside of Tumblr (like Twitter and TikTok) join the platform. Using the phrase “previous tag” or “prev tag” now indexes that one must go to the blog where the post was reblogged to see the tags rather than the tags being copied and pasted into the post or added as a picture. This new evolution of tagging practices makes tagging even more of a semi-private space as people are not even taking the tags and adding them to the post. Instead, creating a rabbit hole of going back a chain of reblogs until you no longer see “prev tag.” Going to the original person who made the amusing tag might help them gain followers, but that does not mean much on a website where no one knows how many followers someone has and there is no financial gain.

Tagging practices on Tumblr disrupt the search system on the platform and change the understanding of the purpose of tagging. Rather than being a form of organization and promotion, there is an intimacy created by “talking in the tags.” While there are tags that do trend, generally tags used for organization, those are organized by Tumblr itself and not necessarily reflective of what people will see as popular on their dashboard. The disconnect between organizational tagging and “talking in the tags” means that posts pertaining to a specific topic may be very popular but ignored by the search system. Avoiding searchability goes against everything tagging was originally intended for and makes creating a history of tagging practices on Tumblr much more difficult. Abandoned, disabled, and shared blogs already make crediting the creator of concepts on the platform difficult to knowledge production and preservation. The frequent inability to track down the originators of concepts and posts directly confronts the temporariness of social media, where something can exist one second and be deleted the next.

“Talking in the tags” on Tumblr uses the tagging system to create a semi-private space on an otherwise wholly public platform. Using tags in this way is different than most other platforms and actively disrupts search functions. While Tumblr is not a platform one can get famous on and then profit, there is still status that comes with having funny tags, and “talking in the tags” is often encouraged by blogs where their purpose is to provide a prompt for users to answer in the tags. Looking at tagging strictly on Tumblr recontextualizes tagging as not a means of promotion or linking oneself to a larger conversation but as a personal aside to a larger discussion that is not inherently meant to be seen by everyone.

Works Cited

Bourlai, E. E. (2018). ‘Comments in tags, please!’: tagging practices on Tumblr. Discourse, context & media, 22, 1-11.

Daer, A. R., Hoffman, R., & Goodman, S. (2014, September). Rhetorical functions of hashtag forms across social media applications. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM international conference on the design of communication CD-ROM (pp. 1-3).

Zappavigna, M., & Martin, J. R. (2018). # Communing affiliation: Social tagging as a resource for aligning around values in social media. Discourse, context & media, 22, 1-9.

That’s All Folx: Does Adding an ‘X’ Make A Word More Neutral?

Abstract

Building off recent research on gender-neutral language, this paper will examine the use of folks and folx concerning usage and perceived neutrality. Since the rise in awareness of non-binary identities and how greetings such as guys and dudes are inherently masculine, thus marginalizing both women and non-binary individuals, there has been an increased need for a gender-neutral way to address groups of people. One suggestion is to use the word folx, which is a variation of the word folks where the ‘-ks’ is replaced with an ‘-x.’ Using “folx incorporates the x that is being widely used to bring in more identities to conversations, such as womxn, Latinx, and alumx” (Robertson, 2018: 47), thus adding to a tradition of using ‘x’ or ‘-x’ to show inclusivity. This paper argues that the use of folx is meant to index the support of non-binary individuals and show inclusivity through language. However, it is not any more or less neutral than the original folks and is not viewed as a better alternative. To assess the perceived neutrality of both folks and folx, I created a survey that was distributed through social media such as Swampy Memes for TWAMPy Teens, Swampy Memes for LGBTQ Teens, and my personal social media accounts. The survey first gauges the perceived gender of various words such as guy, dude, womxn, women, and so on. Then it focuses on the experience’s participants have with both folx and womxn along with why they chose to use that specific spelling and their perception of each word. Finally, the survey concludes with demographic information to determine which group is most likely to use folx than folks along with the social media site they use the most. I found that the use of folx is not widespread nor is it used outside of LGBT+ communities, but its usage is a way to index support and recognition of non-binary individuals. Even though folks is just as neutral and more common than folx the ability to purposefully show social awareness and use fewer characters are the driving forces behind why people use folx.

Introduction

As the awareness of non-binary and gender non-conforming identities rises, there has been a shift to using non-gendered language when referring to a group of people. The shift has caused greetings like guys to fall out of use in favor of words like folks. Online, there has been another shift from using folks to using a variation where the ‘-ks’ is replaced with an ‘-x,’ thus making the spelling folx. Using “folx incorporates the x that is being widely used to bring in more identities to conversations, such as womxn, Latinx, and alumx” (Robertson, 2018: 47), thus adding to a tradition of using ‘x’ or ‘-x’ to show inclusivity. While initially, the change does not appear to make the word more neutral, this paper argues that the use of folx is meant to index the support of non-binary people. However, that spelling is not more inclusive or neutral than folks, and the overall popularity of the term will not increase due to the original spelling already being perceived as neutral.

Literature Review

To understand the need for gender-neutral language it is important to understand what it means to be gender variant. As an umbrella term non-binary “defines several gender identity groups, including (but not limited to): (a) an individual whose gender identity falls between or outside male and female identities, (b) an individual who can experience being a man or woman at separate times, or (c) an individual who does not experience having a gender identity or rejects having a gender identity” (Matsuno and Budge, 2017). One identity that falls under ‘non-binary’ is ‘genderqueer’ which Monroe (2005) defines as “any type of trans identity that is not always male or female. It is where people feel they are a mixture of male and female” (13). While non-binary falls under the label of transgender which Stryker defines as “people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth, people who cross over (trans-) the boundaries constructed by their culture to define and contain that gender” (2008; 1) which allows for non-binary people to use the transgender label if they so choose. The main difference between binary transgender people and non-binary transgender individuals is that binary transgender people identify wither either of the binary genders, either male or female, while non-binary people identify beyond the binary.

Gender-neutral language “has been identified not only by feminists seeking to deemphasize gender and promote inclusivity but by many members of transgender communities who seek a language that will aid them in expressing identities that fall outside of the binary genders of male and female” (Hord 2016; 1) which would allow for a more inclusive way to speak. Having an identity acknowledged in speech is “very important to one’s ability to have their identity understood by others and recognized in everyday speech interactions” (Hord 2016; 1) and if a person’s identity is not being mirrored back to them, then they are being invalidated. For transgender individuals, which includes nonbinary people, “being misgendered – having someone prescribe an incorrect gender to you through the use of a pronoun or gendered term – is a prominent issue” (Hord 2016; 3) that is seen as a sign of disrespect. Misgendering groups can occur in the “practice of using words like woman and man to refer interchangeably to a person’s physiology (e.g. ‘women’s bodies’), childhood socialization (e.g. ‘how women are raised’), perceived gender (e.g. ‘women often experience street harassment’) and gender identity (e.g. ‘women may be inclined to have other women as friends’)” (Zimman 2017; 86) and this same idea applies to group greetings.

Often “overtly gendered nouns, such as woman, female, girl and lady or man, male, guy and dude” are used in casual greetings and to address groups which “function in large part to index the gender of the referent” (Zimman 2017; 89) and being inherently gendered as male or female thus ostracizes non-binary people within the greeting. A prime example of overtly gendered nouns to refer to a group of people is the word dude. In Kiesling’s (2004) research on the usage of dude, he found “that dude is a term that indexes a stance of cool solidarity for everyone and that it also has second orders of indexicality relating it to young people, young men, and young counter-culture men” (300). The inherent association of dude with men and masculinity is a reason the term has been deemed as not gender-neutral. Even though dude “is used mostly by young men to address other young men [and] its use has expanded so that it is now used as a general address term for a group (same or mixed gender) and by and to women” (Kiesling 2004; 282) the indexing to maleness still leaves the term heavily gendered in the eyes of many. The word guys has the same problem as dude, where it can be perceived neutrally but is still heavily gendered.

For those who are against gendered greetings, the solution is the use of folks as it does not have the heavily gendered connotation that guys and dudes have. Nevertheless, there have been instances of the word folx being used instead of folks. The addition of an ‘-x’ to indicate gender neutrality and inclusivity is not a new concept and has gained popularity through terms such as Latinx1. There are “some cultural commentators claim that the word “Latinx” emerged around 2004 from queer communities on the Internet who favored a non-binaristic gender-inclusive term” (DeGuzmán, 2017; 216) but the exact conception of the term cannot be defined due to how it has only recently gained mainstream popularity. From a linguistics standpoint with Spanish being a grammatically gendered language using ‘-x’ as a suffix act “to gender neutralize the term, while also providing a term for those who are transgender or queer” and “offers a decent alternative to [the] unnecessary imposition of gender” (de Onis, 2017; 81-82). Even though there is some debate in the public sphere over the function of -x within the Spanish language, DeGuzmán argues that it works in both Spanish and English, where “in Spanish, the denomination becomes “Latineh-kees” and in English “Latin-x”” (2017; 217). DeGuzmán also argues that “by substituting an “x” for the usual binary gender terminations “o,” “a,” “o/a,” and “a/o,” attention is shifted away from binaries to the more open-ended, ambiguous “x.” This “x” can mean anything. It is the “x” of an algebra in which any value may be assigned” (2017; 220), and for some people, that can feel liberating. Explicitly using ‘-x’ can index an awareness and care towards “social justice for queer and non-gender-conforming bodies” and in the case of folx using the ‘-x’ can be “about making a public and political statement” (de Onis, 2017; 85) much like using Latinx. There is also the view that “the “x” functions as a marker of presence—particularly of presence in a space” (DeGuzmán, 2017; 220) which can be applied more broadly to include the use of “x” in other words to show the existence of a minority and therefore allowing them to take up space which is what the “x” in folx is doing.

This same process of changing the spelling of a word to reflect one’s stance on a social issue can be seen with changing the spelling of women to womyn and, more recently, to womxn2. In the spring of 1991, the Random House Webster’s College Dictionary, “widely publicized as the first “politically correct” dictionary,” added womyn as an alternate spelling to women” (Steinmetz, 1995; 430). At the same time womyn was being excluded from the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language and Anne Soukhanov, the executive editor at the time, justified the decisions because “the evidence showed that it is used chiefly in the literature of women’s issues and that when it does occur in general sources, more often than not it is enclosed in “shutter quotes” or briefly glossed, often in a jocular manner” (Steinmetz, 1995; 430) which caused the editors to believe the word had not yet gained widespread usage. As Steinmetz points out in his article, womyn had been cited on many occasions between 1976 and 1994, with some of the articles justifying the usage of womyn instead of women. For example, the “Shanties, Shakespeare, and Sex Kits: Confessions of a Dartmouth Review Editor” from the Fall of 1989 views the usage as “another feminist operating technique in the avoidance of the words “man” and “his.” Thus, women become “wimmin,” “womyn,” and, most frequently, “womben”” (Steinmetz, 1995; 433). Many of the sources cite the use of womyn as a way to “take the ‘men’ out of ‘women’” (Steinmetz, 1995; 434), which is the main reason for the alternate spelling. Although it should be noted that there is not a consistent idea of how to remove the men from women and Steinmetz found that “North American users prefer the spelling womyn whereas British users opt for wimmin” but “both spellings, however, seem to have originated in the United States in the mid-1970’s”(1995; 437). Other justifications of the change in spelling include using “the alternate spelling of women (wimmin) as a means of self-empowerment and as a political stance against the patriarchy which we as wimmin face on a daily basis” (Burnett, 1998; 33) and the more recent use of ““womxn” as a symbol of resistance to move beyond a monolithic, white-dominant, cisgender, man-centered understanding of “womxnhood” and move toward a more inclusive and empowered meaning” (Ashlee, Zamora, & Karikari, 2017; 102). The change in spelling that women underwent appears to be the same processes that folks is experiencing with a variation that puts a spotlight on social justice.

Methodology

To research the perceived neutrality of folks versus folx, I distributed a survey across my personal Facebook page, Twitter page, and two William and Mary Facebook groups called Swampy Memes for TWAMPy Teens and Swampy Memes for LGBTQ Teens. The survey begins with participants ranking the words: guys, y’all, girls, folx, men, women, folks, womxn, everyone, dudes, ladies, boi, and gurl on a zero to five scale. On the scale, zero is very masculine, five is very feminine, and three is completely neutral. Then participants were asked about their usage and experiences with the words folx and womxn since they both utilize an ‘x.’ I chose to use womxn instead of Latinx because it removed the possible variable of grammatical gender and focused on the alternate spelling of words that did not require a spelling change. For both terms, participants were asked if they have ever seen them used instead of the original spelling, folks, or women/woman, and then if they have ever used the alternate spellings. If they have used the alternate spellings, they were asked why, and if not, they were asked why they think someone would use the alternate spellings. The survey then concludes with demographic information such as age, race, gender, sexuality, and most frequently used social media sites since the popularization of folx appears to have happened online.

Findings

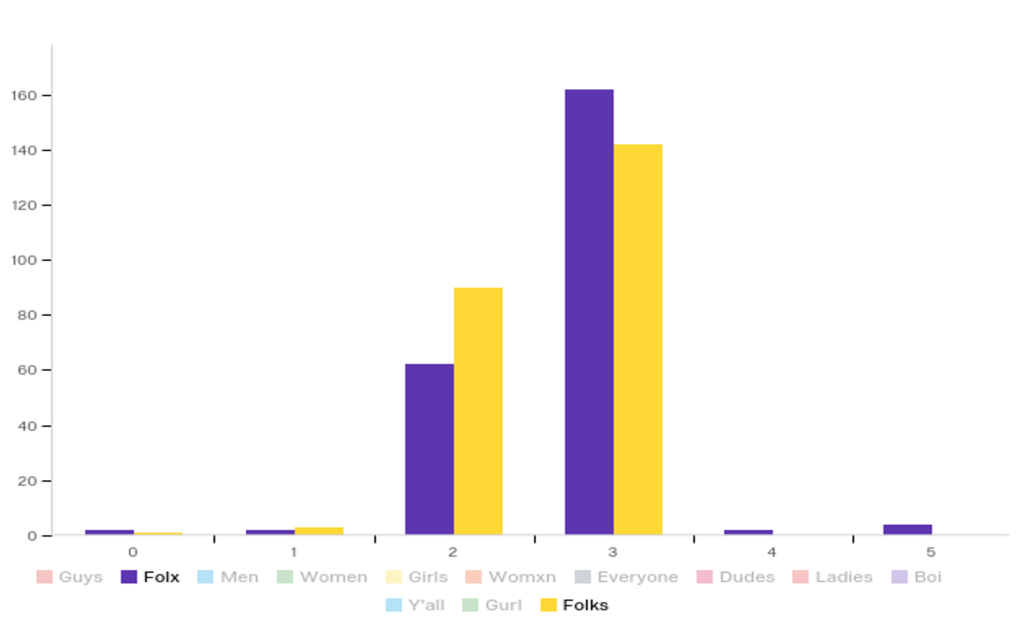

This survey garnered 273 responses in total between October 24th, 2019, and November 18th, 2019. In the first task on the survey (figure 1), both folx and folks had a majority neutral rating (around a two or three on the provided scale), but out of the 273 participants, 162 ranked folx as a three while 142 ranked folks as a 3. Also, four participants ranked folx as masculine (a zero or one), and six ranked it as feminine (four or five), no one ranked folks as feminine, and four people ranked it as masculine. So, 82% of participants perceived folx as neutral while 85% perceived folks as more neutral.

Despite both being perceived as neutral only 28.27% of participants have ever encountered folx being used to address a group of people, and only 17.91% have ever used folx instead of folks. For those who have used folx to refer to a group of people, the two main reasons for doing so are seeing folx as more inclusive and showing support for nonbinary people. The second most popular reason is that participants saw other people using folx instead of folks and started doing so. One participant said “I like it aesthetically, but I wouldn’t use it in a formal context. I don’t see it as being more inclusive than “folks”” and another uses folx because it uses “fewer characters for Twitter.”

As for the perception of using folx instead of folks, most participants felt like someone would use the former to be more inclusive, followed by using it to make a political statement. 32 participants selected ‘other’ and wrote in their opinion on why someone would use folx. One participant saw the change from folks to folx as “adding an x in to fit in with Latinx and such – I guess it’s more inclusive to nonbinary people? But Folks in of itself is super neutral. Seems redundant. And I’m pretty far left,” yet the main reason participants wrote in is, as one person put it, “to seem more inclusive even though folks works just as well.” Two respondents felt as though the alternate spelling exists “because people take southern ways of speaking and then change them because they’re mf dummies” and “to remove the rural, conservative stigma surrounding folks.” Another sentiment people brought up is how people use folx “because they think it makes them more woke,” which is to say that the person using it appears more socially aware and “to signal to readers that they’re committed to inclusivity.” Finally, an idea brought up is that folx is used “because they don’t realize that folks is already neutral.” One participant said, “I have never seen any explanation where folx makes sense instead of folks – it’s ALREADY neutral.” Accounting for sexuality within this data out of the 28.27% who have seen folx used to refer to a group of people 73.13% identify as LGB+ and 28.33% being transgender or nonbinary. As for those who have used folx, all of them are LGBT+.

Demographically, a large majority of respondents are between the ages of 18 and 30, with a statistically insignificant amount being older than 30. Meaning, that those responding to my survey are mainly college students and/or people in their 20’s since that is who is in the Facebook groups I posted the survey on and my general friend group. Racially 83.77% of the participants are white, which is not surprising considering that a majority of William and Mary is white, and most of the people I am friends with on Facebook are white due to where I grew up. For gender, 68.09% of respondents identify as cisgender women, 20.43% identify as cisgender men, and 11.48% identify as transgender or nonbinary. As for sexuality, 50.42% of participants identify as heterosexual, with the rest identifying as LGBT+. Finally, the most used social media site is Facebook, followed by Instagram and Twitter.

Discussion

Originally, I expected to find more people being aware of the usage of folx, but only slightly more than a quarter of my sample has ever seen it and even less have ever used it. Unsurprisingly though, a vast majority of people who have encountered folx and all of those who use the term are LGBT+, which makes sense considering the term appears to circulate a lot on LGBT+ social media. Like womyn, folx appears to be mostly used in feminist and LGBT+ circles, causing the lack of awareness and usage by outsiders, in this case, mainly heterosexual people. Now there is a possibility that the cisgender, heterosexual culture at large, has not caught on to the use of folx to index support of non-binary people, but that is unlikely due to folks being seen as just as neutral and inclusive.

As noted by a few of my respondents, the shortening of folks to folx could also be a result of character limits on social media platforms such as Twitter. By being able to replace -ks with -x a person saves one character they could use elsewhere. It was also brought up that people saw the usage of folx as a performative act where the point was not to be more neutral but instead to show off their social awareness towards nonbinary people and being performatively inclusive to make a point. Also, out of all the social media options, the only one referenced to by name for those who have seen and used folx is Twitter. If folx originated on Twitter and started as a way to save characters in a tweet then, it is possible that the association with showing support for non-binary people was tacked on later as a reaction to Latinx. However, overwhelmingly, those who participated in my survey saw folx as a performative act rather than as shorthand for folks. By positioning folx as simply a social performance, it is possible that the term will only be used by niche online communities. Folx being a performative act online would also make sense because the pronunciation of folx and folks is exactly the same, so the way one would write the word becomes negligible when talking.

Unlike the usage of Latinx where a gender-neutral version of Latino/Latina is needed, the use of folx is seen as unnecessary due to folks already being neutral. As some of my participants wrote in, the addition of folx appears redundant because folks is already neutral, and according to the data from the first task on the survey, both terms are perceived with the same level of neutrality. They seemed to dismiss its usage as just a way to take something that is not an issue, folks not being inclusive enough, and making it more inclusive. Although one respondent raised the point that folks tends to have a very Southern and conservative connotation, which might be why people felt the need to change the spelling to distance themselves from appearing Southern and conservative. A further point of research could be comparing y’all and folks as gender-neutral greetings through the perception of Southerness since the use of y’all appears to have increased on social media. The co-opting of the lexical feature of Southern dialects combined with the distaste form said dialects could be a contributing factor to changing the spelling of folks.

Overall there are no strong feelings towards folx; instead, it is treated like a spelling variation some people choose to use. There is an understanding that its purpose is to be inclusive of non-binary people, but there has not been any major push to use folx or any harsh judgment being passed either way. While the sample I collected is not reflective of the greater population of those online or in the world advocating for the use of folx, it appears as if a very small number of people regularly encounter it or feel the need to use it. Since folks is just as neutral and more widely used, folx will most likely fall into obscurity like womyn and only be used by a niche group of people for a specific purpose causing it to not spread to the rest of society.

Conclusion

While folx and folks are perceived as equally neutral, the ability to index support for non-binary people is the main draw towards using folx. Even though many feel as though the usage is redundant and there is no widespread usage outside of LGBT+ spaces, it is too early to say whether folx is a fad or not. My data only represents a small number of mostly college-aged individuals and was not distributed to larger LGBT+ online platforms so opinions might differ outside of the researched sample. The usage of neutral language to address groups of people is still important, and figuring out ways to address groups without assuming everyone’s gender is still tricky, but substituting folks for folx is not how people are going about it. Neutral and inclusive language is important, which is why there has been a rise in the usage of words like Latinx, but when an already neutral word like folks gets changed, people feel less inclined to change their spelling habits. Overall, people will use folx, whether it is to save on Twitter characters or to show support for non-binary people. However, the original folks is still viewed as the preferred spelling that is more likely to continue to be used by a majority of people.

[1] There are op-eds being written where the usage of Latinx is being brought into question. Some people suggest using Latine instead, while others feel as if neither is necessary.

[2] The use of womxn is much more recent than the use of womyn or wimmin, which is why there is no scholarly research on it. However, many news media outlets have articles referencing the use of womxn as a more inclusive version of womyn. The issue with womyn is the association with TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) ideology that views gender as essential, and therefore, transgender people are just confused and do not exist. While the use of womxn has not been around enough to be studied in an academic fashion my inclusion of it in this paper is meant to reference it is used in non-academic environments.

Bibliography

Ashlee, Aeriel, Bianca Zamora, & Shamika N Karikari. (2017): We Are Woke: A Collaborative Critical Autoethnography of Three “Womxn” of Color Graduate Students in Higher Education. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19.1 89-104.

Burnett, L. (1998). Different youth, different voices: Perspectives from young lesbian wimmin. Children Australia, 23(1), 33-37. doi:10.1017/S103507720000849X

de Onis, Catalina. (2017). What’s in an “x”?: An Exchange about the Politics of “Latinx”. Chiricú Journal: Latina/o Literatures, Arts, and Cultures. 1. 78. 10.2979/chiricu.1.2.07.

DeGuzmán, M. (2017). Latinx: ¡Estamos aquí!, or being “Latinx” at UNC-Chapel Hill. Cultural Dynamics, 29(3), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374017727852

Hord, L. C. (2016). Bucking the Linguistic Binary: Gender Neutral Language in English, Swedish, French, and German. Western Papers in Linguistics/Cahiers linguistiques de Western, 3(1), 4.

Kiesling, S. F. (2004). Dude. American Speech, 79(3), 281–305. doi: 10.1215/00031283-79-3-281

Matsuno, E. & Budge, S.L. (2017) “Non-binary/Genderqueer Identities: a Critical Review of the Literature” Curr Sex Health Rep 9: 116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0111-8

Monro, S. (2005). Gender Theory. In Gender Politics: Citizenship, Activism and Sexual Diversity (pp. 10-42). LONDON; ANN ARBOR, MI: Pluto Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt183q5wt.6

Robertson, N. (2018). The Power and Subjection of Liminality and Borderlands of Non-Binary Folx. Gender Forum, (69), 45-76.

Steinmetz, S. (1995). Womyn: The Evidence. American Speech,70(4), 429-437. doi:10.2307/455626

Stryker, S. (2008). Transgender history. Seal Press.

The Digital Object The Digital World

Preface: I wrote this piece for a class on multimodal ethnography I took in fall 2021. The assignment was to study the materiality of an item and its cultural significance. As an avid gamer and lover of all things Animal Crossing I contemplated the ways in which the buying, selling, and trading of items on Animal Crossing New Horizons were culturally significant to Facebook communities.

Animal Crossing New Horizons just updated with 9,000 new items. Within the game, players can buy items from Nook’s Cranny (the general store on the island), build them themselves with DIY recipes, or through the ATM in the residence center. But outside of the game, there is a whole network of people who buy, sell, and trade Animal Crossing items. For example, Nookazon is a website dedicated to buying and selling items for currency within the game. At the same time, some people have started small businesses selling DIY recipes and items for out-of-game money. In addition, some communities have formed out buying, selling, and trading of items along with groups where people show off how they decorated their island with said items.

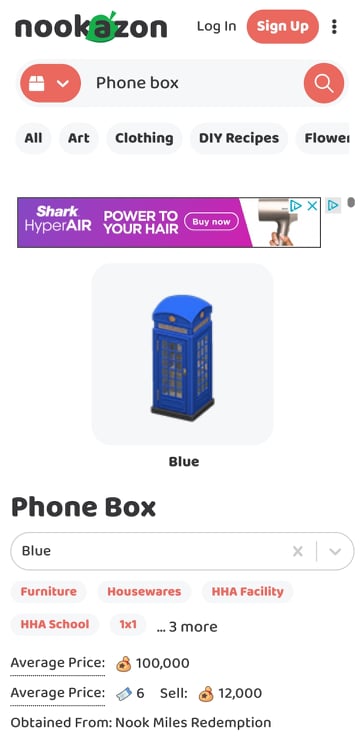

Part of the appeal of buying items from other people is due to color variations within the game—some items a person can only buy in one color because they are specific to their island. For example, through the ATM in the residence center, a player can exchange Nook Miles (a form of in-game currency) for items like a Phone Box (figure 1), which only comes in one color option that cannot be changed. If a player does not like the default color option on their island, they can exchange with other players who might have the color they want, which is where Nookazon comes in (figure 2 & 3). The exchange of digital objects is part of the appeal of the game, players want their island to look nice, and by exchanging items, relationships are formed. Physically the only objects being handled in person by the player is their Nintendo Switch, but within the game, the many objects can be manipulated.

The game’s limitations dictate where items can and cannot be placed, which places boundaries on how objects can be used. Even if there is counter space, gameplay limits might not allow for items to be put on that surface. While the entire island is, for the most part, customizable, the size of objects is measured by squares (figure 4 &5) where two objects cannot be placed in the same square or on the line between squares. These limitations significantly impact how players, and most specifically their avatar, interact with items. A player can have an item, but it could be functionally useless without the space to display it. Despite the item’s size, they can be held in the avatar’s “pockets,” yet the item cannot be placed or turned without enough room on the island. The “pockets,” while holding items of any size, also have a capacity limit that one must pay in-game to expand. Another limit is the use of tools; as one uses a tool to modify their island, the tool breaks down until the player must buy another one. Unlike other objects in the game, where once you have it in your possession, nothing will happen to it, tools must be constantly constructed or purchased because they will break.

Most items in Animal Crossing New Horizons are a digital representation of a real-life item. Objects like mugs, stoves, plants, and the like can be found in a user’s everyday life. There are also culturally specific objects related to holidays like an ox figurine (figure 6) to celebrate Chinese New Year, which might not be a specific offline object but relates to events offline. Since Animal Crossing has a global market, events and items targeted to various cultures are incorporated. For example, the Brazilian celebration of Carnival is an event within the game that includes the collection and display of multiple items to “prepare” for the event. These items are also island-specific, with buy, sell, and trade groups discussing which color and version they have and what items they want.

Certain items become symbolic of the game within digital communities, like the “Froggy Chair” (figure 7), which was not a part of the original Animal Crossing New Horizons game but was added in the latest update critical reference points. The excitement players expressed when it was revealed that the “froggy chair” was being released was immense. Before the item was in the game, players would discuss their longing for a “froggy chair” and how they missed it from previous games. As far as I am aware, very few people have recreated a “froggy chair” in the physical world, yet there is communal importance of the “froggy chair.” Through buying, selling, trading, and discussing objects in Animal Crossing, communities are formed, generally through social media but possibly in person, thus contributing to the connection of many players to each other.

Some players run islands specifically to catalog items. The process for using a catalog island is as follows: travel to the island, find the item you want, pick it up, put it down, repeat with any other items, and go back to your island to buy them through the NookShopping application. Islands used strictly for cataloging are often very utilitarian, and the codes to travel to them are kept to smaller Animal Crossing communities. The acts of picking up an item (thus having the item in one’s possession) and then putting it down tells the game the player can now have access to purchasing the item in-game. When on the ground, items are shaped like a leaf (figure 8 & 9), which does not represent an item but the concept of an item. Going to an island to catalog items is strictly interacting with the representation of the items. The play picks up and puts down the leaf to be able to buy the item later. Processes like this where the primary interaction is with the representation of an item bring up a larger question of what it means to own a digital object.

As more parts of life become digital, the way digital material is discussed becomes essential. To have a digital object is different from owning a physical object since the person does not experience the object’s physical nature. When I buy an object in Animal Crossing, I can only consider what it could be like if it were a physical object. My avatar can hold and manipulate the object, but I am still only touching my Nintendo Switch (figure 10). In a way, this is like NFT’s and cryptocurrency, where the possession of digital art or money only occurs in the digital. I cannot hold cryptocurrency in my hand and physically exchange it with another person, much like the items in Animal Crossing cannot be physically held. Likewise, when people cannot see each other in person due to distance or a global pandemic, Animal Crossing provides a place to meet up even if no item exchange happens.

Meeting people and hanging out in the digital world is nothing new; Tom Boellstroff writes about digital communities in his book Coming of Age in Second Life, but COVID forcing everyone to move their communication online sheds a different light on the issue. The interactions and material exchanges players have within Animal Crossing New Horizon are all digitally mediated and have limitations due to the nature of the game. However, there is still a material culture within the game. Simply seeing a picture of the object of one’s desire is not enough but having that object on one’s island is the ideal. Not having a specific object or a beloved object like the “froggy chair” available in-game is less than ideal for most players. Some go as far as to exchange real-world money for objects within the game which underscores the value of digital items to players.

The question becomes, what does it mean to own an object digitally, and how can these objects be discussed when existence is strictly within the digital world? Animal Crossing New Horizons demonstrates how video games and digital worlds with their own material culture create communities of people who connect over the objects. All objects in Animal Crossing are digital representations, but they are treated like physical objects through the process of exchange (be it trade or buying). Also, there is a temporariness to digital objects like the ones in Animal Crossing; if your game crashes, you can lose everything, whether you bought the items in-game or through a third party using offline money. Digital worlds and their materials are important to people, be it through games or investing in cryptocurrencies. Digital objects are still objects even if they can not be held and manipulated offline.

Friend of East End: Dr. Ryan Smith

My first semester of graduate school at Brandeis University was Fall 2020. While my expectation was to go up to Waltham, Massachusettes the COVID-19 pandemic had other plans. Starting my joint master’s degree in anthropology and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies in my childhood home made me reconnect with my hometown of Richmond Virginia in a way I have not done since high school. During this time I also started an internship with the podcast This Anthro Life with Adam Gamwell through Brandeis.

With This Anthro Life I learned the ins and outs of podcast production and social media management. We discussed narrative arcs, interviewing skills, and how to figure out your target audience. My final project for the official internship was an interview with Dr. Ryan Smith on his latest book Death and Rebirth in a Southern City: Richmond’s Historic Cemeteries.

Dr. Ryan Smith is a professor of US history, material culture, and historic preservation at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia and a Friend of East End. We met through mutual work with the Friends of East End and at the time of the interview there were multiple issues with Enrichmond blocking the Friends of East End from being able to do their work. Enrichmond wanted the friends, specifically Brian Palmer, to turn over all of their work without getting any credit.

My interview with Dr. Ryan Smith was my first major interview and the first officially public podcast. While it was nerve wrecking thinking about how many people could listen to my podcast it was well received. I currently still run the Instagram for This Anthro Life and make some of the episode art.

Dr. Ryan Smith

Website: https://history.vcu.edu/directory/smith.html

This Anthro Life

Website: https://www.thisanthrolife.org/

Instagram: @ThisAnthroLife

Twitter: @ThisAnthroLife

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/thisanthrolife

Friend of East End: Brian Palmer

When I was in high school my family and I started volunteering at East End Cemetery, a historically Black cemetery on the border of Richmond and Henrico County in Virginia. East End Cemetery was founded in 1897 and abandoned in the 1970’s due to bankruptcy. It was not until the summer of 2013 when efforts to restore East End Cemetery, and its neighboring Evergreen Cemetery, began in full force.

The Friends of East End are a group of volunteers who cleaned up the cemetery every weekend and started an oral history project to document the stories of descendants. Brian Palmer is one of the founding members of The Friends of East End along with his wife Erin Hollaway-Palmer. As a photojournalist, he documented the restoration of East End Cemetery over the years and published a book with Erin documenting their work entitled The Afterlife of Jim Crow: East End and Evergreen Cemeteries in Photography. In 2019 he won a Peabody for Reveal radio story “Monumental Lies” with his collaborator Seth Wessler. I interviewed him in spring 2020 for a digital journalism class I was taking at the time.

Brian Palmer is currently a professor of journalism at Columbia University while still working with The Friends of East End with their current restoration project at Woodland Cemetery. He is also a big fan of rootbeer and his dog Teacake.

East End Cemetery:

Website: https://eastendcemeteryrva.com/

Instagram: @eastendcemeteryrva

Friends of East End

Website: https://friendsofeastend.com/

Instagram: @friendsofeastend

My First Podcast

I made my first podcast in the Fall of 2016. It was my first semester of undergrad at The College of William and I was taking a class called Museums and Identities. One of the projects required us to research a person or place important to the Revolutionary War and, if possible, a part of the 2015 musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda Hamilton. I chose to research John Laurens as he met all of the requirements and was an early supporter of abolition.

Listening back to this podcast years later is strange. I remember recording it in my dorm room with a cheap microphone line by line as I had no experience scripting content. With a pile of books on either side of me and way too many tabs open on my laptop I tried to piece together a compelling and informative story about John Laurens. If I remember correctly I think I got a cold about halfway through recording and tried so hard to make my voice sound like I wasn’t sick!

I also presented it on my 19th birthday and despite some of the audio repeating in parts, it was well-received. Yet over the years, I lost the original audio files when changing laptops and while pursuing podcasting further hadn’t really thought about my first one. Thanks to some digital archaeology in my personal email account I found the closest thing I have to a final edit of my first podcast. So here it is, fresh from the vault, my first podcast!

Hello World!

Hi I’m Sara Schmieder! I’m a project manager at a marketing agency and a Board Member at Large at the Bisexual Resource Center. I graduated from The College of William and Mary with honors in anthropology in 2020, and then in 2022, I graduated with a Master’s Degree in anthropology and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies from Brandeis University. I’ve been online since I was a teenager, and my research centers around digital anthropology. Here are some fun facts about me:

- I love art and make stained glass windows

- I grew up in Richmond, Virginia

- I love fiber arts and spend my free time knitting and crocheting

- Playing video games and watching movies are my two favorite past times

- I have a minor in linguistics and took all but one class for it with the same professor

- In 2019, I performed an original poem about Furbys at a cafe’s open mic night

- It is very rare to see me without earbuds in my ears and an iced coffee in my hand

- I have a Substack called Sara and the Silver Screen where I write about movies and other media